Post by greg on May 31, 2007 8:42:31 GMT -5

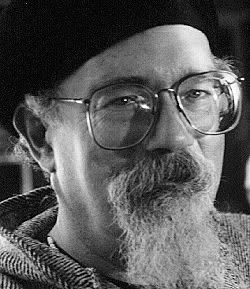

I read a pretty good article on John Sinclair today and thought I would share it....

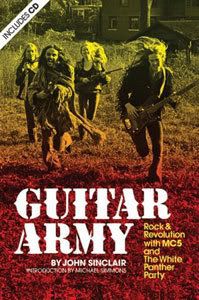

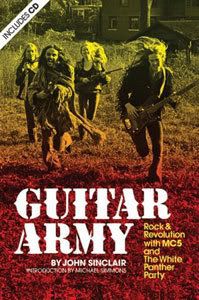

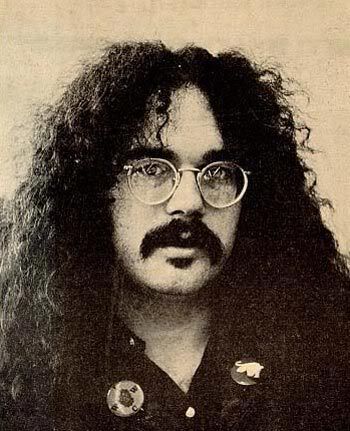

On May 1, 2007 revolutionaries (and hippies) around the world celebrated the 35th anniversary and re-release of John Sinclair's book Guitar Army (Process Media). Originally published in 1972 following Sinclair's release from prison after serving two and a half years of a 10 year sentence for possession of two joints, Guitar Army served as an entire generation's handbook for revolt. So popular - and controversial - the book quickly went out of print and developed into a cult classic. Thanks to Process Media, the new expanded 35th Anniversary edition features 40 previously unreleased photos from the heyday, a new intro by Michael Simmons and a nifty bonus CD with rare recordings from MC5, Uprising, John Sinclair, Allen Ginsberg, Black Panther Bobby Seal, Up! and more.

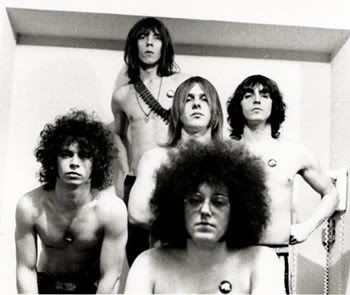

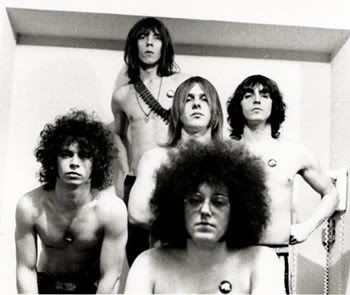

As a young man growing up in Detroit in 1966, Sinclair became the manager of the hugely influential band MC5 (Motor City 5). "The Five," as they were often called, would not only help set the stage for punk and hard rock, they would become the house band of the revolution. In 1968, the MC5 recorded their first album, Kick Out The Jams, which would help ignite a fire that raged against the political and social climate of the day. Coinciding with the album, Sinclair released a statement of the declaration of the White Panther Party. Sinclair, along with the members of MC5 and a select group of fellow revolutionaries, created the White Panther Party to oppose the U.S. government and support the Black Panthers through a "total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock & roll, dope and fucking in the streets."

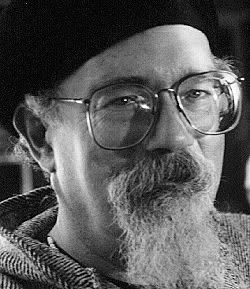

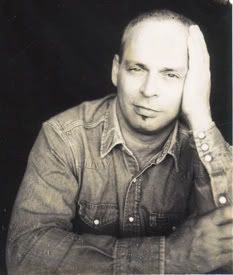

So, how did a young kid from a nice family in Flint, Michigan turn into a revolutionary hero and political prisoner with the likes of John Lennon and Stevie Wonder fighting for his release?

"I just started smoking joints and taking acid and peyote and it lead me into something completely different from where I started from" says Sinclair. "Between that and the black music, I was in a different world. And I've been there ever since, and I ain't leaving!"

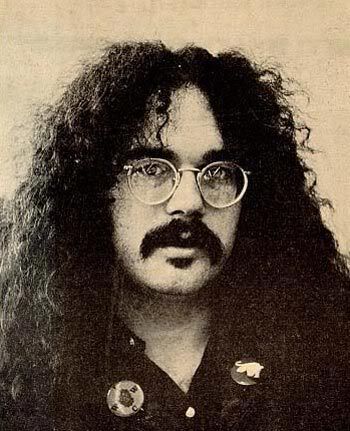

Inside this world of mind-expanding drugs and black (blues and jazz) music, Sinclair was transformed. He became a beacon of light, "the leading intellectual of long-haired people," he claims. And that's exactly what opened up the MC5 to his influence. "John Sinclair was the first guy who wasn't a music business type guy. He was like us, and we respected him," says MC5 guitarist and co-founder Wayne Kramer. "He agreed to join with us to try to see if we could combine our efforts to push our various interests to a higher level."

These were the seeds of the rock & roll revolution. The years that followed are chronicled in Guitar Army. Although Sinclair says, "It's not something I'd write today, but I thought I got my hands on the moment," the book is a necessary record of a movement that changed America.

In 1969, Sinclair was sentenced to almost 10 years for giving two joints to undercover narcotics officers. In 1970, the FBI declared the White Panthers "potentially the largest and most dangerous of revolutionary organizations in the United States." All this during a time when approximately 58,000 American soldiers were dying in Vietnam, and a rough estimate of one million Vietnamese combatants and four million civilians were killed in the war. This was also the time period when John F. Kennedy (November 22, 1963), Malcolm X (February 21, 1965) and Martin Luther King (April 4, 1968) were assassinated. With these events as a backdrop, it was excessive to declare the White Panthers a major threat to America, and it was beyond comprehension to go one step further and send their leader to jail for 10 years for two joints. With blood flowing at home and overseas, America's citizens simply wouldn't stand for it.

In a true testament to the power of rock & roll, The John Sinclair Freedom Rally at Crisler Arena in Ann Arbor, Michigan on December 10, 1971 would be the final step in setting Sinclair free. The eight hour event featured John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Stevie Wonder, Allen Ginsberg, Phil Ochs and many others speaking and performing in front of 15,000 people. Three days later the Michigan Supreme Court released Sinclair and overturned his draconian conviction.

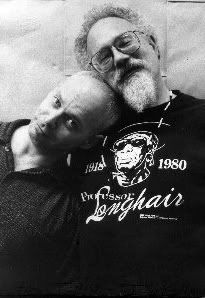

35 years later, both Sinclair and Kramer are appalled at how little has changed. "We're really going backwards," says Sinclair. "It's mind-boggling how the lessons of Vietnam have been absolutely, totally ignored" adds Kramer. "He's [President Bush] trying to find a place in history and the place the he wants so badly he can't have, which is to be remembered as a great leader. He'll be remembered as the great chump, the guy who almost destroyed the country."

Like every generation, the younger people look to past leaders for guidance and answers. So why are we repeating history? "Young people today really seem to be more interested in the mall and a Blackberry and text messaging their friends," says Kramer. "World events, even tragic, immoral wars don't seem to really affect them. Where is the outrage?"

"They have to turn off their TV sets for a while and try to feel something," adds Sinclair. "They have to develop a heart because they've got everything else. They can communicate. They have the World Wide Web. We didn't have anything as great as that. We used to have to print things on a mimeograph machine and hand them out on the street. It's the passion that's missing. They're surrounded by this horrible [mainstream/radio] music and horrible movies and TV and the news and all that shit. It's just created to cocoon people inside."

The advancement of technology is this generation's double-edged sword. We communicate on a level never imagined 35 years ago, yet this same ability to ingest material at such a fast pace leaves the door open to filling our brains with misinformation, propaganda and mind-numbing hours of white noise. Can we leverage technology to push us forward, or will it simply continue to dumb us down and "cocoon" us as Sinclair says?

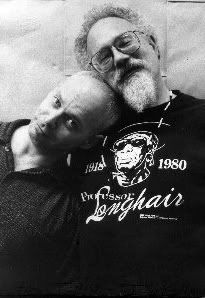

The answer is unclear but in the meantime Sinclair and Kramer aren't going quietly into the night. They still perform together regularly; and on the day I spoke with them, Sinclair read his poetry with Kramer supporting him. Although Sinclair says "rock & roll is not going to be a weapon of culture. I couldn't have been more wrong on that," he still uses music to open minds. Since his release from prison, Sinclair has gone on to become the founder and director of the Detroit Free Jazz Center, a professor of popular music history at Wayne State, worked as the editor for the Detroit Sun newspaper, managed bands, produced concerts and is a revered freelance journalist, poet and bandleader. In 1991, Sinclair moved to New Orleans and became a disc jockey at WWOZ radio, where he was voted the city's most popular DJ five years in a row (1999-2003) by OffBeat magazine's readers' poll. Following a visit to Amsterdam as High Priest of the Cannabis Cup, Sinclair moved to the Netherlands in 2003 and created his influential internet program, "The John Sinclair Radio Show," which is part of RadioFreeAmsterdam.

Of his move to the Netherlands, Sinclair reflects, "If we woulda kept at it some things would be different [in the U.S.]. Like in Holland where I live half the year, people like us kept on and engaged themselves with the political process in a real way, and not just having demonstrations but getting people to vote for a different way. They installed many of our ideas in the fabric of everyday life, like taking care of people. You don't see homeless people in Amsterdam too much."

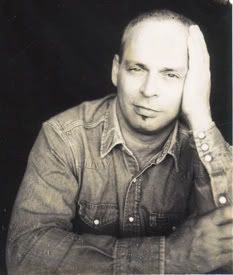

Following the '60s and '70s, Kramer faced his own struggles. "There was certainly a high point in being in the MC5 and a great sense of possibilities and camaraderie and mutual respect of being part of a community," he says. "There were great low points when all that was gone and the whole downward arc where I ended up an alcoholic, drug addict and convict."

In 1975, Kramer was caught selling cocaine to undercover federal agents and spent two years in prison. Upon his release, Kramer stayed out of the public eye and the music business until the 1995 release of his debut solo album, The Hard Stuff. When asked if "The Man" was able to keep him down, and if the demise of the MC5 and his time in prison changed his views, Kramer is quick to respond, "I'm still left of left. I'm not convinced I'm going to change the world today, but that doesn't mean I'm any less passionate about social justice. There are things that are wrong and they're immoral and unethical and they need to be addressed. A spotlight needs to be put on them. There are people and forces in play that are anti-civilization, anti-human rights. The stuff that I think is worth fighting for may not seem glamorous and may not be sexy - things like education, health care, security and democracy. They're not Hollywood ideas, these are human ideas that have been here from the beginning, and I think they're worthy of time and effort. None of that's changed. In fact, if anything I'm more committed."

These days Kramer collaborates with Rage Against the Machine's Tom Morrello, works on movies and is almost finished with another album.

"I'm in it every day," says Kramer. "I'm trying to make something good happen every day." Of his new record Kramer tells us, "It's a big departure. It's all instrumental except for one spoken word piece. It'll be the companion album to the score of a film I'm doing called The Narcotics Farm, which is a documentary investigation into the United States government's treatment of prisoners in the '40s, '50s and '60s in Lexington, Kentucky, where they experimented on prisoners with drugs. Kind of connected to the Tuskegee syphilis experiments and CIA experiments on mind-controlling drugs."

35 years later, Kramer and Sinclair are still fighting the good fight. They love music and are passionate about social justice. Jail time, oppressive governments and years of struggle couldn't keep them down. Today, we're looking for leaders. Perhaps the reissue of Guitar Army can serve as fodder for the next revolution.

"If they had some acid today things would be different," says Sinclair. "It was a catalyst. All of the sudden you penetrated the bullshit and the popular culture and life and you thought, 'This isn't real. The universe is real. The stars are real, the trees are real, but this is horseshit.' That was a great revelation. I'm still working off of the things I learned 40, 45 years later."

www.jambase.com/headsup.asp?storyID=10570&disp=all

On May 1, 2007 revolutionaries (and hippies) around the world celebrated the 35th anniversary and re-release of John Sinclair's book Guitar Army (Process Media). Originally published in 1972 following Sinclair's release from prison after serving two and a half years of a 10 year sentence for possession of two joints, Guitar Army served as an entire generation's handbook for revolt. So popular - and controversial - the book quickly went out of print and developed into a cult classic. Thanks to Process Media, the new expanded 35th Anniversary edition features 40 previously unreleased photos from the heyday, a new intro by Michael Simmons and a nifty bonus CD with rare recordings from MC5, Uprising, John Sinclair, Allen Ginsberg, Black Panther Bobby Seal, Up! and more.

As a young man growing up in Detroit in 1966, Sinclair became the manager of the hugely influential band MC5 (Motor City 5). "The Five," as they were often called, would not only help set the stage for punk and hard rock, they would become the house band of the revolution. In 1968, the MC5 recorded their first album, Kick Out The Jams, which would help ignite a fire that raged against the political and social climate of the day. Coinciding with the album, Sinclair released a statement of the declaration of the White Panther Party. Sinclair, along with the members of MC5 and a select group of fellow revolutionaries, created the White Panther Party to oppose the U.S. government and support the Black Panthers through a "total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock & roll, dope and fucking in the streets."

So, how did a young kid from a nice family in Flint, Michigan turn into a revolutionary hero and political prisoner with the likes of John Lennon and Stevie Wonder fighting for his release?

"I just started smoking joints and taking acid and peyote and it lead me into something completely different from where I started from" says Sinclair. "Between that and the black music, I was in a different world. And I've been there ever since, and I ain't leaving!"

Inside this world of mind-expanding drugs and black (blues and jazz) music, Sinclair was transformed. He became a beacon of light, "the leading intellectual of long-haired people," he claims. And that's exactly what opened up the MC5 to his influence. "John Sinclair was the first guy who wasn't a music business type guy. He was like us, and we respected him," says MC5 guitarist and co-founder Wayne Kramer. "He agreed to join with us to try to see if we could combine our efforts to push our various interests to a higher level."

These were the seeds of the rock & roll revolution. The years that followed are chronicled in Guitar Army. Although Sinclair says, "It's not something I'd write today, but I thought I got my hands on the moment," the book is a necessary record of a movement that changed America.

In 1969, Sinclair was sentenced to almost 10 years for giving two joints to undercover narcotics officers. In 1970, the FBI declared the White Panthers "potentially the largest and most dangerous of revolutionary organizations in the United States." All this during a time when approximately 58,000 American soldiers were dying in Vietnam, and a rough estimate of one million Vietnamese combatants and four million civilians were killed in the war. This was also the time period when John F. Kennedy (November 22, 1963), Malcolm X (February 21, 1965) and Martin Luther King (April 4, 1968) were assassinated. With these events as a backdrop, it was excessive to declare the White Panthers a major threat to America, and it was beyond comprehension to go one step further and send their leader to jail for 10 years for two joints. With blood flowing at home and overseas, America's citizens simply wouldn't stand for it.

In a true testament to the power of rock & roll, The John Sinclair Freedom Rally at Crisler Arena in Ann Arbor, Michigan on December 10, 1971 would be the final step in setting Sinclair free. The eight hour event featured John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Stevie Wonder, Allen Ginsberg, Phil Ochs and many others speaking and performing in front of 15,000 people. Three days later the Michigan Supreme Court released Sinclair and overturned his draconian conviction.

35 years later, both Sinclair and Kramer are appalled at how little has changed. "We're really going backwards," says Sinclair. "It's mind-boggling how the lessons of Vietnam have been absolutely, totally ignored" adds Kramer. "He's [President Bush] trying to find a place in history and the place the he wants so badly he can't have, which is to be remembered as a great leader. He'll be remembered as the great chump, the guy who almost destroyed the country."

Like every generation, the younger people look to past leaders for guidance and answers. So why are we repeating history? "Young people today really seem to be more interested in the mall and a Blackberry and text messaging their friends," says Kramer. "World events, even tragic, immoral wars don't seem to really affect them. Where is the outrage?"

"They have to turn off their TV sets for a while and try to feel something," adds Sinclair. "They have to develop a heart because they've got everything else. They can communicate. They have the World Wide Web. We didn't have anything as great as that. We used to have to print things on a mimeograph machine and hand them out on the street. It's the passion that's missing. They're surrounded by this horrible [mainstream/radio] music and horrible movies and TV and the news and all that shit. It's just created to cocoon people inside."

The advancement of technology is this generation's double-edged sword. We communicate on a level never imagined 35 years ago, yet this same ability to ingest material at such a fast pace leaves the door open to filling our brains with misinformation, propaganda and mind-numbing hours of white noise. Can we leverage technology to push us forward, or will it simply continue to dumb us down and "cocoon" us as Sinclair says?

The answer is unclear but in the meantime Sinclair and Kramer aren't going quietly into the night. They still perform together regularly; and on the day I spoke with them, Sinclair read his poetry with Kramer supporting him. Although Sinclair says "rock & roll is not going to be a weapon of culture. I couldn't have been more wrong on that," he still uses music to open minds. Since his release from prison, Sinclair has gone on to become the founder and director of the Detroit Free Jazz Center, a professor of popular music history at Wayne State, worked as the editor for the Detroit Sun newspaper, managed bands, produced concerts and is a revered freelance journalist, poet and bandleader. In 1991, Sinclair moved to New Orleans and became a disc jockey at WWOZ radio, where he was voted the city's most popular DJ five years in a row (1999-2003) by OffBeat magazine's readers' poll. Following a visit to Amsterdam as High Priest of the Cannabis Cup, Sinclair moved to the Netherlands in 2003 and created his influential internet program, "The John Sinclair Radio Show," which is part of RadioFreeAmsterdam.

Of his move to the Netherlands, Sinclair reflects, "If we woulda kept at it some things would be different [in the U.S.]. Like in Holland where I live half the year, people like us kept on and engaged themselves with the political process in a real way, and not just having demonstrations but getting people to vote for a different way. They installed many of our ideas in the fabric of everyday life, like taking care of people. You don't see homeless people in Amsterdam too much."

Following the '60s and '70s, Kramer faced his own struggles. "There was certainly a high point in being in the MC5 and a great sense of possibilities and camaraderie and mutual respect of being part of a community," he says. "There were great low points when all that was gone and the whole downward arc where I ended up an alcoholic, drug addict and convict."

In 1975, Kramer was caught selling cocaine to undercover federal agents and spent two years in prison. Upon his release, Kramer stayed out of the public eye and the music business until the 1995 release of his debut solo album, The Hard Stuff. When asked if "The Man" was able to keep him down, and if the demise of the MC5 and his time in prison changed his views, Kramer is quick to respond, "I'm still left of left. I'm not convinced I'm going to change the world today, but that doesn't mean I'm any less passionate about social justice. There are things that are wrong and they're immoral and unethical and they need to be addressed. A spotlight needs to be put on them. There are people and forces in play that are anti-civilization, anti-human rights. The stuff that I think is worth fighting for may not seem glamorous and may not be sexy - things like education, health care, security and democracy. They're not Hollywood ideas, these are human ideas that have been here from the beginning, and I think they're worthy of time and effort. None of that's changed. In fact, if anything I'm more committed."

These days Kramer collaborates with Rage Against the Machine's Tom Morrello, works on movies and is almost finished with another album.

"I'm in it every day," says Kramer. "I'm trying to make something good happen every day." Of his new record Kramer tells us, "It's a big departure. It's all instrumental except for one spoken word piece. It'll be the companion album to the score of a film I'm doing called The Narcotics Farm, which is a documentary investigation into the United States government's treatment of prisoners in the '40s, '50s and '60s in Lexington, Kentucky, where they experimented on prisoners with drugs. Kind of connected to the Tuskegee syphilis experiments and CIA experiments on mind-controlling drugs."

35 years later, Kramer and Sinclair are still fighting the good fight. They love music and are passionate about social justice. Jail time, oppressive governments and years of struggle couldn't keep them down. Today, we're looking for leaders. Perhaps the reissue of Guitar Army can serve as fodder for the next revolution.

"If they had some acid today things would be different," says Sinclair. "It was a catalyst. All of the sudden you penetrated the bullshit and the popular culture and life and you thought, 'This isn't real. The universe is real. The stars are real, the trees are real, but this is horseshit.' That was a great revelation. I'm still working off of the things I learned 40, 45 years later."

"John Sinclair" by John Lennon

It ain't fair, John Sinclair

In the stir of breathing air

Won't you care for John Sinclair?

In the stair of breathing air

Let him be, set him free

Let him be like you and me

They give him ten for two

What else can the judges do?

Gotta, gotta... gotta, set him free

If he had been a soldier man

Shooting gooks in Vietnam

If he was the CIA

Selling dope and making hay

He'd be free, they'd let him be

Breatthing air, like you and me

They gave me ten for two

What more can the judges do?

Gotta, gotta... gottta set him freee

Was he jailed for what he done?

Representing everyone

Free john now, if we can

From the clutches oof the man

Let him free, lift the lid

Bring him to his wife and kids

They gave me ten for two

What more can the bastards do?

Gotta, gotta... gotta set him free...

It ain't fair, John Sinclair

In the stir of breathing air

Won't you care for John Sinclair?

In the stair of breathing air

Let him be, set him free

Let him be like you and me

They give him ten for two

What else can the judges do?

Gotta, gotta... gotta, set him free

If he had been a soldier man

Shooting gooks in Vietnam

If he was the CIA

Selling dope and making hay

He'd be free, they'd let him be

Breatthing air, like you and me

They gave me ten for two

What more can the judges do?

Gotta, gotta... gottta set him freee

Was he jailed for what he done?

Representing everyone

Free john now, if we can

From the clutches oof the man

Let him free, lift the lid

Bring him to his wife and kids

They gave me ten for two

What more can the bastards do?

Gotta, gotta... gotta set him free...

www.jambase.com/headsup.asp?storyID=10570&disp=all